Our paper FREE to download here

Science & Medicine in Sports

Translating science into effective practice

Tuesday, April 9, 2019

Monday, April 8, 2019

Not every load is risky for an injury

|

| Figure: Load (resulting stress), frequency and injury risk. |

Hello All. Here I'm again after a long absence. Today, I would like to drop few lines on load, frequency and injury risk relationship. I'm stimulated from the recent consensus statement on load and injuries in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. To download this paper click this link here. Great read.

Looking at figure 1 of that paper, I would like to add that not all loads are risky for an injury. Actually, the combination of load and frequency could affect the injury risk. Here is my drawing from the basics in biomechanics. Hope it's clear and you enjoy this read too!

Friday, October 5, 2018

Liverpool vs Manchester City: Who are ready for selection?

The Liverpool vs Manchester City match will definitely attract most of the interest this weekend. Both teams have competed for the UEFA Champions League mid-week and this makes things slightly complicated. Are all players ready for selection? I tried to replicate a hypothetical scenario having player A and B and assuming they are both equally important for tactical reasons. I have applied simple sports science tools and is not my intention to interfere with coach role. The coach has the final word! This is just an example of how sports science could help in decision-making.

No doubt to implement a system like this you need first to build human relationships. To read more on that visit https://www.tandfonline.com/…/full/10…/24733938.2017.1377845 and https://hiitscience.com/coach-lets-do-hiit-today-hmm-not-a…/

Wednesday, September 26, 2018

“Coach, let’s do HIIT today!” “Hmm, not a good idea”.

We now have the program. Our next step is to read behind

the lines before we talk to the coach. With that being said, I’d like to put

forth some hidden issues that are like to arise when you defend your plan to

the coach.

Injuries

“Aren’t we at higher risk of injury doing HIIT compared

to conventional football training”? The answer is both yes and no. We are at

higher risk when we do HIIT if we haven’t respected the basic rule of progressive

overload, which is fundamental to safe exercise training periodization. We

recently showed this in a study, where conventional football training was complemented

with adjacent HIIT sessions (Paul et al., 2018). Across 4 weeks, endurance

performance was improved and no injuries occurred. It’s important to appreciate

that injuries can be the consequence of lower than optimal fitness due to

inadequate training. Indeed, the model proposed by Tim Gabbett suggests that low

fitness itself may be a risk factor for non-contact injuries. In contrast, high

levels of fitness may protect against injuries (Gabbett, 2016). Thus, a focus

towards ensuring high aerobic fitness in our players should actually protect

them from non-contact injury occurrence. Of course, this only occurs when we

build the training program in a progressive manner.

Our

limited resource – Time

It’s important to appreciate that coaches have program to

run. They are concerned more about training as a team, not as individual

player. They have to be. That’s why today, most of our training time in

football uses small-sided games (SSG), which are useful for building and maintaining

match-specific technical and tactical elements (Lacome et al., 2018). Additionally,

we know that playing SSG will assist to develop some of the match specific

physical fitness elements at the same time. With full respect to use of this

approach, SSG have limitations too. For example, SSG might not be specific

enough to a player’s individual needs. Often, SSG won’t provide enough stimulus

to build key football-specific elements like the ability to perform long

intensive efforts.

The solution?

Supplement your SSG with specific short

interval HIIT. For example, you might use 2-3 sets of repeated 15-sec or 30-sec

bouts at 90-95% of maximal speed (Billat et al., 2001a & b; Iaia et al., 2008). Another

option would be to perform repeated bouts of either 30 sec at 110% of 30-15

intermittent field test (IFT) or 15 sec at 120% of IFT (Paul et al., 2018). All

programmes do not require much time and bring great benefit.

After convincing yourself, the next step is to convince

the coach. That’s either the easy or the hard part of the day, depending on

your relationship. I’m talking about the human relationship, because that’s the

foundation of any professional relationship. Building trust is key. I can’t emphasize

the importance of this enough, or give you advice on how to go about this. Its

personal. Ultimately, the ability to build trust in human relationships

incorporates everything; who you are, where you come from, what your life

expectations are, your values and beliefs – ultimately seeing the other person

for who they are and they, in turn, seeing you. Are you there on the team to

satisfy your personal inner needs and professional ambitions, or are you there to

contribute to making the common team dream a reality? Do you believe science is

everything or do you feel we are part of the team, a member of the family, where

using science can help to make it better?

Of course there are theories from the social sciences,

like the diffusion of innovation theory, which can help you further build your

skills in effective communication of science. For those interested please read a recent editorial on this topic (Nassis, 2017). I’m not sure if it is so much

knowing the science behind or trusting your intuition. After so many years, I

tend to believe sometimes it’s good to trust your intuition, provided you have

enough experience to trust in it, it will lead you in the right direction.

Going back to where we started. Maybe instead of “Coach,

let’s do HIIT today”! How about we try another approach with a subtle change in

wording:

“Coach, what do you think about doing HIIT today? Do you

like the plan? Any ideas on how we could make it better?”

This post was first published at HiitScience on September 22, 2018

References

Billat LV. Interval training for performance: a scientific and empirical practice. Special recommendations for middle- and long-distance running. Part I: aerobic interval training. Sports Med 2001a;31:13-31.

Billat LV. Interval training for performance: a scientific and empirical practice. Special recommendations for middle- and long-distance running. Part II: anaerobic interval training. Sports Med 2001b;31:75-90.

Buchheit M, Laursen PB. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle:Part I: cardiopulmonary emphasis. Sports Med 2013;43:313-338.

Buchheit M, Laursen PB. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle.Part II: anaerobic energy, neuromuscular load and practical applications.

Sports Med 2013;43:927-954.

Burgomaster KA, Hughes SC, Heigenhauser GJF,

Bradwell SN, Gibala MJ. Six sessions of sprint interval training increasesmuscle oxidative potential and cycle endurance capacity in humans. J Appl Physiol 2005;98:1985-1990.

Gabbett TJ. The training injury paradox:should athletes be training smarter and harder? Br J Sports Med 2016;50:273-280

Iaia FM, Thomassen M, Kolding H, Gunnarsson T, Wendell J, Rostgaard T, Nordsborg N, Krustrup P, Nybo L, Hellsten Y, Bangsbo J. Reduced volume but increased training intensityelevates muscle Na+-K+ pump alpha1-subint and NHE1 expression as well as short termwork capacity in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol

2008;294:R966-74.

Lacome M,

Simpson BM, Cholley Y, Lambert P, Buchheit M.

Small-SidedGames in Elite Soccer: Does One Size Fit All? Int J

Sports Physiol Perform 2018;13:568-576.

Nassis GP. Leadership in science and medicine: can you see the gap? Science and Medicine in Football 2017;3:195-196.

Paul DJ, Marques JB,

Nassis GP. The effect of a concentrated period of soccer specific fitnesstraining with small-sided games on physical fitness in youth players. J Sports

Med Phys Fitness 2018 Jun 27 [Epub ahead of print]

Tuesday, September 25, 2018

Decelerations, accelerations, total workload and return to play: food for thought

Today, I had the chance to read a fantastic recent editorial on the nature of decelerations in football and their contribution on player's mechanical load. Here is the link to the full paper which I hope you enjoy.

With this opportunity, I had also the time to think more about the topic. No doubt that decelerations as well as accelerations should be taken into account when quantifying player's workload. With full respect to the great work published and despite the advances in knowledge regarding isolated risk factors for injuries, one of the key questions remains unanswered: what constitutes workload in football and team-sport athletes? Which indices should we trust in order to build effective injury risk estimation models? A couple of years ago we published an editorial with the hope to stimulate further discussions on the topic. I believe this paper is still relevant and hope you enjoy this read too https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/51/6/486

Monday, May 14, 2018

Real world research worth exploring: Machine learning algorithms in injury prevention

In the study of López-Valenciano, a total of 132 male professional soccer and handball players underwent pre-season screening evaluation which included personal, psychological and neuromuscular measures. In addition, injury surveillance was employed to all musculoskeletal injuries during the season. The authors employed different learning techniques to check their accuracy in injury prediction.

Their results showed that the machine learning algorithms presented moderate accuracy for identifying players at risk of injury. From other studies, we know that ML accuracy can be improved with more data entered in the analysis. Nevertheless, the novelty of the study of López-Valenciano and colleagues is they showed that machine learning can assist in solving problems like the identification of players at risk. However, one should bear in mind that ML algorithms work well for the population they were created and we cannot predict what will happen with another set of data.

Tuesday, May 8, 2018

Real world research worth exploring: Accelerometer-based prediction of sports injury

|

| analog.com |

The use of accelerometers in studying the non-contact injury risk is a hot topic both in team and individual sports. Recently a research team from the University of California tested the hypothesis that the running-related injuries were the result of a combination of high load magnitude and strides number that result in accumulated microtrauma (Kiernan et al., 2018). During the studying period of 60 days, elite runners wore a hip-mounted activity monitor to record accelerations while training. From these accelerations the researchers estimated the vertical ground reaction forces (vGRFs). Their results showed that the injured athletes had significantly greater peak vGRFs and weighted cumulative loading per run.

The beauty of this study is the use of a common accelerometer to derive data associated with injury risk. Of course, these findings should be verified in bigger samples but the main message of this study is that this type of microtechnology, much cheaper that the GPS-embedded accelerometry, may assist in injury risk management for athletes/teams with limited resources.

Wednesday, May 2, 2018

Player performance metrics: time to reconsider our approach!

There are different performance metrics but most of them are looking at football performance in a fragmented way. For instance, match running distance at different speeds is considered as an important index, sometimes without taking into consideration the match context (player's position, opposition performance etc).

Also, it seems that some actions, very decisive for the team performance, are not properly evaluated. As an example, in one moment in last night's match Bayern Munich striker defended very effectively against Ronaldo (at 6th minute of the match, match highlights here ).

How would you rate an attacker's performance doing fantastic work while team is defending? Is it time to reconsider our approach and integrate physical performance with technical and tactical data? Your thoughts?

Monday, February 5, 2018

How to test your players? 如何测试你的运动员的健身?

Fitness testing in football (soccer) can be a useful tool to 1) identify individual's needs, 2) reduce the risk of injuries, and 3) optimize training plans and performance. There is a number of tests that a sport scientist and practitioner can use. Before you choose, it would help if you answer the following questions:

-Why am I testing the players?

-What is my plan for the next month and the whole season?

-Which of the tests in the literature are valid, reliable and sensitive to training?

-Which of those that fulfill criterion 3 above, does my coach like?

To make it simple for you, I have summarized in table 1 below the most common tests. Their validity and reliability varies a lot and should you want to know the in-depth details you can read table 2 as well as our review paper on that topic (Paul & Nassis, 2015a). In general, all the below tests have acceptable validity and reliability.

While this is a guide, I advise you, especially the junior practitioners, before you go ahead and speak to the coach, better to have plan B too. Sometimes coaches may prefer a different test to the ones on the list.

Table 2. Summary of the tests advantages and disadvantages (modified Paul & Nassis, 2015a)

Sources & related links

Bangsbo et al (2008). Sports Medicine 38(1): 37-51, read here

Buchheit (2008). Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 22(2): 365-374, read here

Huijgen et al. (2010). Journal of Sports Science 28(7): 689-698, read. here

Paul, Gabbett & Nassis (2016). Sports Medicine 46(3): 421-442, read here

Paul & Nassis (2015a). Pediatric Exercise Science 27(3): 301-313, read here

Paul & Nassis (2105b). Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 29(6): 1748-58, read here

-Why am I testing the players?

-What is my plan for the next month and the whole season?

-Which of the tests in the literature are valid, reliable and sensitive to training?

-Which of those that fulfill criterion 3 above, does my coach like?

To make it simple for you, I have summarized in table 1 below the most common tests. Their validity and reliability varies a lot and should you want to know the in-depth details you can read table 2 as well as our review paper on that topic (Paul & Nassis, 2015a). In general, all the below tests have acceptable validity and reliability.

While this is a guide, I advise you, especially the junior practitioners, before you go ahead and speak to the coach, better to have plan B too. Sometimes coaches may prefer a different test to the ones on the list.

Table 1. Common tests used for fitness assessment in football (soccer)

Football Fitness Element

|

How to test?

|

Where can I find more info to back up my proposal?

|

10-m, 20-m, 30-m, 40-m sprint

|

||

Huijgen et al (2010)

|

||

Repeated Sprint Ability

|

7 X 30m or 6 X 20m

|

|

Dribbling ability

|

Huijgen et al (2010)

|

|

Table 2. Summary of the tests advantages and disadvantages (modified Paul & Nassis, 2015a)

Sources & related links

Bangsbo et al (2008). Sports Medicine 38(1): 37-51, read here

Buchheit (2008). Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 22(2): 365-374, read here

Huijgen et al. (2010). Journal of Sports Science 28(7): 689-698, read. here

Paul & Nassis (2015a). Pediatric Exercise Science 27(3): 301-313, read here

Paul & Nassis (2105b). Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 29(6): 1748-58, read here

Thursday, January 11, 2018

Coach, better to do whole body cryotherapy or cold water immersion?

This is a frequently asked questions by players and competitive athletes

after they have completed prolonged and exhaustive exercise. Should you have

the resources available in your club, this is a true dilemma. Both forms of

cryotherapy, either whole body cryotherapy (BC) or cold water immersion (CWI)

are used to speed up recovery. The suggested mechanism of potential beneficial

effect of cryotherapy is associated with reduced inflammation, muscle damage

and muscle soreness perception. Whether or not cryotherapy assists in a faster

recovery of the functional capacity and sports performance is still debatable.

Whole body cryotherapy is gaining more popularity and this

is due to the fact with this form of cryotherapy athletes can be exposed to far

higher temperatures compared to CWI (around -85 °C vs. -10 °C).

This level of air temperature during the whole BC is assumed to limit inflammation

by reducing peripheral blood flow and, hence, speed up recovery after

exhaustive exercise. However, there is very little evidence to support this

assumption. Therefore, the effect of whole BC vs CWI is still under investigation.

In a recent study, published in the European Journal

of Applied Physiology, 31 trained but recreational runners completed a test

marathon and following the run they were allocated in 3 groups in terms of the

recovery means they used: the CWI group, that immersed lower limbs and iliac

crest at water of 8 °C for 10 min; the whole BC group, that was exposed to two

cold treatments in a cryotherapy chamber (3 min at − 85 °C followed by a 15-min warming period in ambient temperature + 4-min bout at − 85 °C); and the placebo group. Participants

in the placebo group consumed 2 × 30 ml per day of a fruit flavored drink

which did not contain any antioxidants or phytonutrients 5 days before the run,

in the day of the run and for 2 days after. In this group, participants were simply

asked to rest in ambient temperature for 10 min following completion of the marathon.

The results of this study showed that the implementation of

a cryotherapy intervention resulted in at least unclear effects for every

outcome measure when compared to the placebo intervention. As the authors state

in their manuscript it seems that any beneficial effect of cryotheraphy after

exercise is simply a product of the placebo effect.

These findings support the idea of planning the recovery strategy

that best fits the beliefs and the needs of the individual athlete.

Source

Wilson et al (2018). Recovery following a marathon: a

comparison of cold water immersion, whole body cryotherapy and a placebo

control. European Journal of Applied Physiology 118:153-163.

Tuesday, January 2, 2018

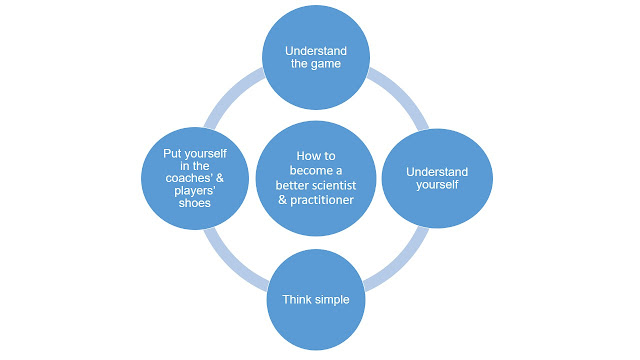

The best scientists get out and talk to the coaches

Are you a sport scientist and medical team member wondering why the coaches can't understand you? To make you feel better let me say you are not the only one. In a survey with high level football club staff it was reported that their injury prevention programs' effectiveness was lower than initially expected. The reason being the low coaches' engagement (1).

As many would agree there is a gap between the staff in the lab and the treatment room and the coaches. Sometimes or most of the times they don't speak the same language. What can we do? Let's start with small changes. The first step is to get out of the lab and talk to the coaches. Talk to them using a language they can understand. Talk when it's needed and communicate what's important. Day by day communication will build trust. Trust will build confidence in your relationship and, with time, trust and confidence will make things better.

The figure below is a short description of steps that could help in making the connection between team members stronger. Should you want to read more on tips of more effective communication you can read this article

For further reading

1.Akenhead and Nassis (2016). Training load and player monitoring in high-level football. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 11(5): 587-593 here

As many would agree there is a gap between the staff in the lab and the treatment room and the coaches. Sometimes or most of the times they don't speak the same language. What can we do? Let's start with small changes. The first step is to get out of the lab and talk to the coaches. Talk to them using a language they can understand. Talk when it's needed and communicate what's important. Day by day communication will build trust. Trust will build confidence in your relationship and, with time, trust and confidence will make things better.

The figure below is a short description of steps that could help in making the connection between team members stronger. Should you want to read more on tips of more effective communication you can read this article

|

| Figure 1. Four tips to become a better professional. |

For further reading

1.Akenhead and Nassis (2016). Training load and player monitoring in high-level football. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 11(5): 587-593 here

Thursday, July 27, 2017

Why RPE is not the best tool to identify athletes in risk of injury?

Published

J Strength Cond Res. 2017 Aug;31(8):e77-e78. doi:

10.1519/01.JSC.0000522116.12028.06

Reply to Manuscript

Clarification for the paper:

Brito J, Hertzog M,

Nassis GP. Do match-related contextual variables influence training load in

highly trained soccer players? J Strength Cond Res 30:393-399, 2016.

Title:

Workload assessment in

soccer: an open-minded, critical thinking approach is needed

George P. Nassis1, Maxime Hertzog1 and

Joao Brito2

We

acknowledge the journal for giving us the opportunity to highlight the key

findings and clarify any misunderstandings to the authors (1). Our practical

advice that “coaches need to take into consideration that training loads are

affected by match-related parameters“ is based on actual data which showed that

1) higher weekly loads were reported after a defeat or draw compared to a win,

and 2) when preparing to play against a medium level team, average sRPE during

the week was higher than that before playing against a top or bottom team (2).

With reference to the first point, we commented in the paper that “it was not

possible to conclude whether this was a consistent coaching strategy or whether

it denoted the difficulty the coaches have to create training sessions as

demanding as official matches”.

Our

findings are in line with the literature showing that the complex interaction

of many factors that contribute to the personal perception of physical exertion,

including hormonal and neurotransmitters concentration, substrate levels,

external factors (environment, spectators), psychological states, previous

experience and memory may limit the use of RPE in accurately quantifying

training intensity and workload (3, 4). This might explain the high variability

we found in sRPE (5–72%). Objective methods, like heart rate monitoring, are

suggested as a more accurate way of internal workload calculation. The limitations

of RPE use in soccer have also been presented elsewhere, with the correlation

coefficients between sRPE and heart rate-based training load ranging from

0.50–0.61 (5).

Regarding

the second point of this letter stating that the training content of our study

was not controlled, we believe this point has been made clear in our

manuscript. In fact, this is one of the limitations of sRPE; the fact that no

account is taken for the external load. As mentioned on the letter, the authors

“are aware that such a study design is almost impossible to set at elite soccer

level” (1). Therefore, there is no disagreement between the letter’s authors

and us.

In

summary, our study showed that a RPE-based workload calculation is not without

limitations and this should be taken into account from scientists and

practitioners. Indeed, this point has been raised by others as well (3, 4).

Studies showing low-to-moderate correlation coefficients between RPE and

GPS-derived workload data are on the same line (6). As mentioned by the

letter’s author previously, “despite various contributing factors, session

rating of perceived exertion has the potential to affect a large proportion of

the global sporting and clinical communities” (7). We believe our

study has indeed highlighted some of these “contributing factors”. As we

acknowledge in our manuscript, “the sRPE is a practical low-cost tool to assess

training load in soccer”. However, this does not justify that it can be an

accurate and sensitive method in all cases, and all its limitations should be

considered. Either subjective or objective data should be combined, or one

should move towards assessing the training physiological outcome and eliminate

the use of subjective tools, especially with elite players (8, 9). There is a

risk of spreading inappropriate information by presenting RPE-based method as

the gold standard for workload quantification. We strongly suggest a more

open-minded and critical thinking approach to the related data presented in the

literature. This approach might help advance the knowledge in the field which

at the moment is superficial and of limited extent.

References:

1.

Chamari

K, Tabben M. Manuscript clarification. J

Strength Cond Res, 2017.

2. Brito

J, Hertzog M, Nassis GP. Do match-related contextual variables influence

training load in highly trained soccer players? J Strength Cond Res 30: 393-399, 2016.

3. Borresen J, Lambert MI. The

quantification of training load, the training response and the effect on

performance. Sports Med 39:779-795,

2009.

4. Abbiss

CR, Peiffer JJ, Meeusen R, Skorski S. Role of ratings of perceived exertion

during self-paced exercise: what are we actually measuring? Sports Med 45:1235-2143, 2015.

5. Impellizzeri

FM, Rampinini E, Coutts AJ, Sassi A, Marcora SM. Use of RPE-based training load in soccer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 36: 1042-1047,

2004.

6. Weston

M, Siegler J, Bahnert A, McBrien J, Lovell R. The application of differential

ratings of perceived exertion to Australian Football League matches. J Sci Med Sport 18:704-708, 2015.

7. Haddad M, Padulo J,

Chamari K. The usefulness of session rating of perceived exertion for

monitoring training load despite several influences on perceived exertion. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 9: 882-883, 2014.

8. Akenhead

R, Nassis GP. Training load and player monitoring in high-level football:

current practice and perceptions. Int J

Sports Physiol Perform 11: 587-593, 2016.

9. Nassis GP, Gabbett

TJ. Is workload associated with injuries and performance in elite football? A

call for action. Br J Sports Med

51:486-487, 2017.

Monday, June 5, 2017

Friday, May 12, 2017

Tuesday, May 2, 2017

Monday, May 1, 2017

The Transition Period in Soccer: A Window of Opportunity

Below is a review paper we published last year with relevant points and practical advises. Should you are interested in learning more please click on the link here and send me an email. Limited copies will be provided. The infographic is by Dr Yann Le Meur.

Sports Med. 2016 Mar;46(3):305-13. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0419-3.

The Transition Period in Soccer: A Window of Opportunity.

Silva JR, Brito J, Akenhead R, Nassis GP

Abstract

The Transition Period in Soccer: A Window of Opportunity.

Silva JR, Brito J, Akenhead R, Nassis GP

Abstract

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)