How many times have you heard this? Let’s do HIIT to make

us feel better? It’s not uncommon. High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) is popular, but in fact its popularity

resides mostly amongst the scientists. Coaches are more conservative, and fear implementation

of HIIT, at least as it is described in scientific papers. Indeed, the very

first studies of the revised HIIT model from Canada described a HIIT protocol with

repeated 30-sec all-out bouts on the bike while pedaling against an external

load of 0.075 kp per kg body weight (Burgomaster et al., 2005). As the area

evolved, more real-world protocols were developed (Iaia et al., 2008). Here, participants

performed 8-12 x 30 sec bouts at 90-95% of their maximal running speed, with

3-min rest between. Billat et al. (2001a & b) proposed another programme that consists of repeated

15 sec high intensity bouts with 15 sec of low intensity or rest in between. I believe we are now in a position to say that we have

some realistic proposals to put on the table for consideration by coaches. Martin

and Paul have further advanced our knowledge, proposing easy to use protocols

and ideas (Buchheit & Laursen, 2013a & b), which will be extended further

in the book and course across 20 sport application chapters provided by

practitioners embedded at the coalface of elite sport.

We now have the program. Our next step is to read behind

the lines before we talk to the coach. With that being said, I’d like to put

forth some hidden issues that are like to arise when you defend your plan to

the coach.

Injuries

“Aren’t we at higher risk of injury doing HIIT compared

to conventional football training”? The answer is both yes and no. We are at

higher risk when we do HIIT if we haven’t respected the basic rule of progressive

overload, which is fundamental to safe exercise training periodization. We

recently showed this in a study, where conventional football training was complemented

with adjacent HIIT sessions (Paul et al., 2018). Across 4 weeks, endurance

performance was improved and no injuries occurred. It’s important to appreciate

that injuries can be the consequence of lower than optimal fitness due to

inadequate training. Indeed, the model proposed by Tim Gabbett suggests that low

fitness itself may be a risk factor for non-contact injuries. In contrast, high

levels of fitness may protect against injuries (Gabbett, 2016). Thus, a focus

towards ensuring high aerobic fitness in our players should actually protect

them from non-contact injury occurrence. Of course, this only occurs when we

build the training program in a progressive manner.

Our

limited resource – Time

It’s important to appreciate that coaches have program to

run. They are concerned more about training as a team, not as individual

player. They have to be. That’s why today, most of our training time in

football uses small-sided games (SSG), which are useful for building and maintaining

match-specific technical and tactical elements (Lacome et al., 2018). Additionally,

we know that playing SSG will assist to develop some of the match specific

physical fitness elements at the same time. With full respect to use of this

approach, SSG have limitations too. For example, SSG might not be specific

enough to a player’s individual needs. Often, SSG won’t provide enough stimulus

to build key football-specific elements like the ability to perform long

intensive efforts.

The solution?

Supplement your SSG with specific short

interval HIIT. For example, you might use 2-3 sets of repeated 15-sec or 30-sec

bouts at 90-95% of maximal speed (Billat et al., 2001a & b; Iaia et al., 2008). Another

option would be to perform repeated bouts of either 30 sec at 110% of 30-15

intermittent field test (IFT) or 15 sec at 120% of IFT (Paul et al., 2018). All

programmes do not require much time and bring great benefit.

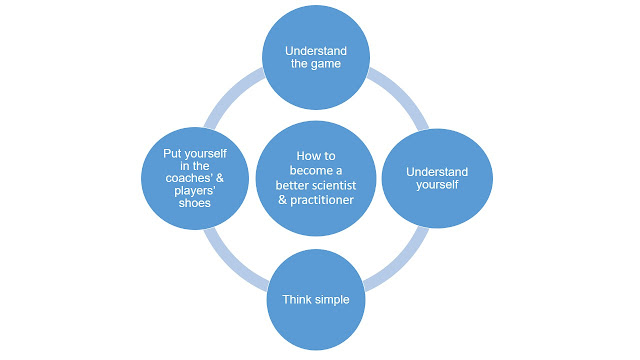

After convincing yourself, the next step is to convince

the coach. That’s either the easy or the hard part of the day, depending on

your relationship. I’m talking about the human relationship, because that’s the

foundation of any professional relationship. Building trust is key. I can’t emphasize

the importance of this enough, or give you advice on how to go about this. Its

personal. Ultimately, the ability to build trust in human relationships

incorporates everything; who you are, where you come from, what your life

expectations are, your values and beliefs – ultimately seeing the other person

for who they are and they, in turn, seeing you. Are you there on the team to

satisfy your personal inner needs and professional ambitions, or are you there to

contribute to making the common team dream a reality? Do you believe science is

everything or do you feel we are part of the team, a member of the family, where

using science can help to make it better?

Of course there are theories from the social sciences,

like the diffusion of innovation theory, which can help you further build your

skills in effective communication of science. For those interested please read a recent editorial on this topic (Nassis, 2017). I’m not sure if it is so much

knowing the science behind or trusting your intuition. After so many years, I

tend to believe sometimes it’s good to trust your intuition, provided you have

enough experience to trust in it, it will lead you in the right direction.

Going back to where we started. Maybe instead of “Coach,

let’s do HIIT today”! How about we try another approach with a subtle change in

wording:

“Coach, what do you think about doing HIIT today? Do you

like the plan? Any ideas on how we could make it better?”

This post was first published at H

iitScience on September 22, 2018

References